6.6 Biochemical Basis of Dominance

Given that a heterozygote’s phenotype cannot simply be predicted from the phenotype of homozygotes, what does the type of dominance tell us about the biochemical nature of the gene product? How does dominance work at the biochemical level? There are several different biochemical mechanisms that may make one allele dominant to another.

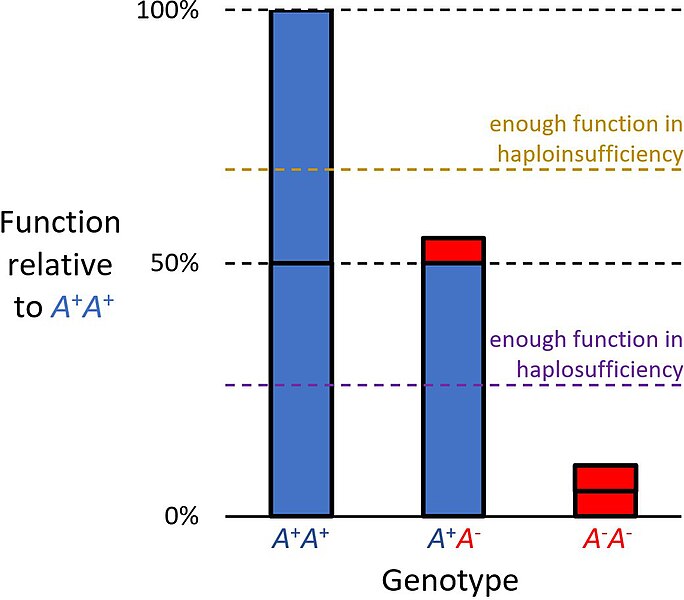

For the majority of genes studied, the normal (i.e., wild-type) alleles are haplo-sufficient. So in diploids, even with a mutation that causes a complete loss of function in one allele, the other allele — a wild-type allele — will provide sufficient normal biochemical activity to yield a wild type phenotype and thus be dominant and dictate the heterozygote phenotype.

On the other hand, in some biochemical pathways, a single wild-type allele is not enough protein and may be haplo-insufficient to produce enough biochemical activity to result in a normal phenotype, when heterozygous with a non-functioning mutant allele. In this case, the non-functional mutant allele will be dominant (or semi-dominant) to a wild-type allele.

Mutant alleles may also encode products that have new and/or different biochemical activities instead of, or in addition to, the normal ones. These novel activities could cause a new phenotype that would be dominantly expressed.

Media Attribution

- Figure 6.6.1 Haploinsufficiency graph only by Adrian J. Hunter, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Long Description

- Figure 6.6.1 The haploinsufficiency model of dominant genetic disorders: A+ is a normal allele and A- is a mutant allele with little or no function. In haplosufficiency (most genes), a single normal allele provides enough function, so A+A- individuals are healthy. In haploinsufficiency, a single normal allele does not provide enough function, so A+A- individuals have a genetic disorder. [Back to Figure 6.6.1]